Life, for me, was once punctuated by the regular delivery of letters and packages from a friend I had never met. You must know how remarkable the sender was. A busy, elderly, man he had experienced exalted stations in his long life. He was the late anthropologist, Ashley Montagu—one of the world’s brightest minds to shed light on the human condition. In particular, Ashley Montagu stood to understand and articulate scientifically what constitutes the well-being of individuals, cultures, and society as a whole.

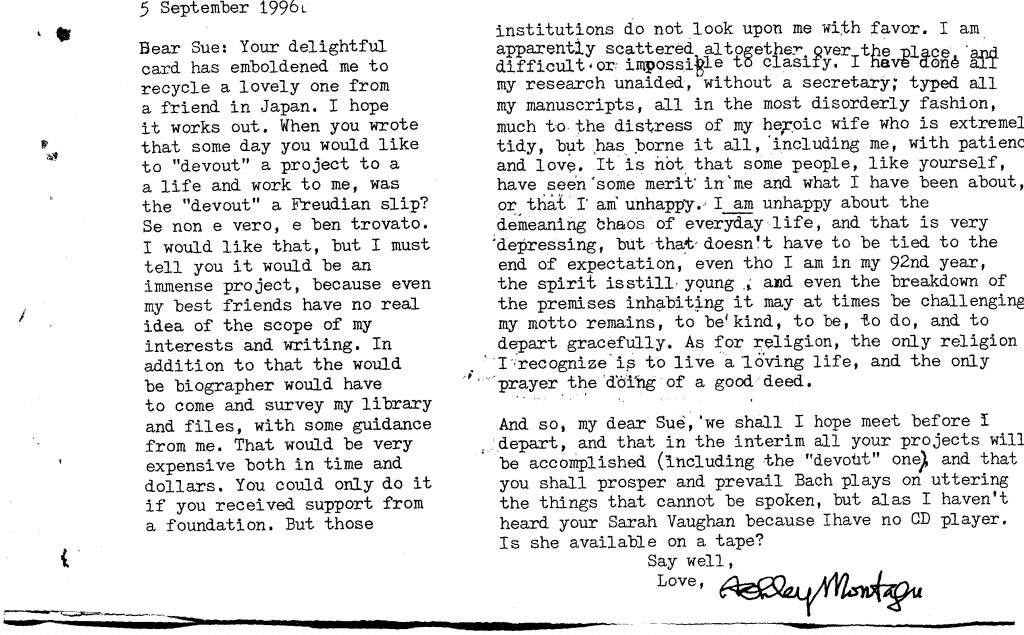

Ashley often used the salutation “Stay well.” You see it intended in the letter above, but for a slip of the pen producing “Say well” instead. As Ashely asks me in this letter, yes, that was undoubtedly a Freudian slip. As my conscious desire was, indeed, to be devout in reviving Montagu’s proclamations. Likewise, he has his Freudian slip with “Say well”.

To say “well” must be to speak of wellness, which is where Montagu placed much of his attention, and for which he became a “well” of information. His hope was to entice a wellspring of action in support of policies and values that ensure and teach human rights. To him life was meant to live in a well manner. As he asserts here, “… the only religion I recognize is to live a loving life, and the only prayer the doing of a good deed.” Ashley always employed scientific reasoning in defining what it meant to be well, to be healthy, and successful. He defined love as: “the active process of communicating to the other by demonstrative acts of your profound involvement in their welfare such that you give them all encouragement, sustenance, support and stimulation that they require, for their unique fulfillment.”

The New York Times obituary wrote that Ashley Montagu was full of “energy, erudition, and showmanship . . . a freelance commentator on nearly everything human.” His life was not ordinary, nor short, nor surely without renown. To the contrary, he was known the world over, for decades on end, as the voice of reason, compassion, and equal access. His provocative arguments found a stage on bookshelves and television sets with willing audiences. Montagu’s works were often controversial. Although, as Steven Harnad (2000) reminds us in his obituary in “Evolutionary Psychology”: “If some of his ideas . . . appear to be relatively uncontroversial and a matter of common knowledge and assent, let it not be forgotten that that very knowledge and assent is in some measure due to the work and efforts of Montagu.”

He wrote on subjects as far ranging as anatomy, genetics, disabilities, human aggression, child development, genital mutilation, nuclear non-proliferation, the fallacy of race, and the specific genetic strengths of women. I first became familiar with him through his book Touching. It lent credibility to claims made in a parenting manuscript I would soon be soliciting to publishers. Since it was my first effort in the field, I sought critical reviews by noted authorities. What was astounding was the swift receipt of Ashley’s positive review.

Our correspondences grew to include little gifts and chocolates. He requested I send him Mother See’s soft caramel chocolates, in exchange for books and such from his enormous library. To say it was a precious mentoring understates the effect. It was through his urging that I pursued an advanced degree in anthropology. In retrospet, understanding the human condition and how it is that we embody well-being had always been my life-long quest. Now a master, with incredible integrity, was my teacher.

Ashley lived by the motto he liked so much to quote: that people should “live as if to live and love were one”. He held the expectation that society ought to facilitate this imperative by enacting family-friendly policies–the paramount importance to humankind being the development of the individual through their innate capacity for learning and flexibly adapting (known as plasticity).

At the forefront of all his research and writing was the acceptance that variation is the rule of our human nature. Montagu also told the story of Joseph Merrick–The Elephant Man, which helped to usher in human rights for the physically challenged. For him, there was an urgency to prove that cruelty is not at our core, even though it is evident all around, what tempers it is socially contingent and thus our responsibility to discover and use.

Ashley wrote to me that the book he authored which pleased him most was Growing Young. This book (one of more than 60) discusses 26 basic behavioral needs that must be met if we are to obtain the quality of health and well-being we all desire and our minds develop to their most efficient potential.

The Basic Behavioral Needs

1. Love 15. Flexibility

2. Friendship 16. Experimental-Mindedness

3. Sensitivity 17. Explorativeness

4. Think Soundly 18. Resiliency

5. To Know 19. Sense of Humor

6. To Learn 20. Joyfulness

7. Work 21. Laughter and Tears

8. Organization 22. Optimism

9. Curiosity 23. Honesty and Trust

10. Wonder 24. Compassionate Intelligence

11. Playfulness 25. Song

12. Imagination 26. Dance

13. Creativity

14. Openmindedness

To paraphrase Montagu’s message–when adults retain these traits linked with childhood, the rate of development slows down and so extends the phases of development from birth to old age. It is our human nature, he asserted, to always remain in a state of development. He argued that the human species is designed to behave in body, spirit, emotion, and deportment in a way that allows for maturation in a manner that celebrates childhood characteristics.

Montagu asked the question: Are adults and children two independent classes of social beings? He urged us to look to our children for answers, for it is by the depth of their possibilities that children out distance adults in the amount they implicitly know about growing. This belief and vitality is what drew many readers and students to embrace Montagu’s philosophy on positive human aging throughout the life cycle.

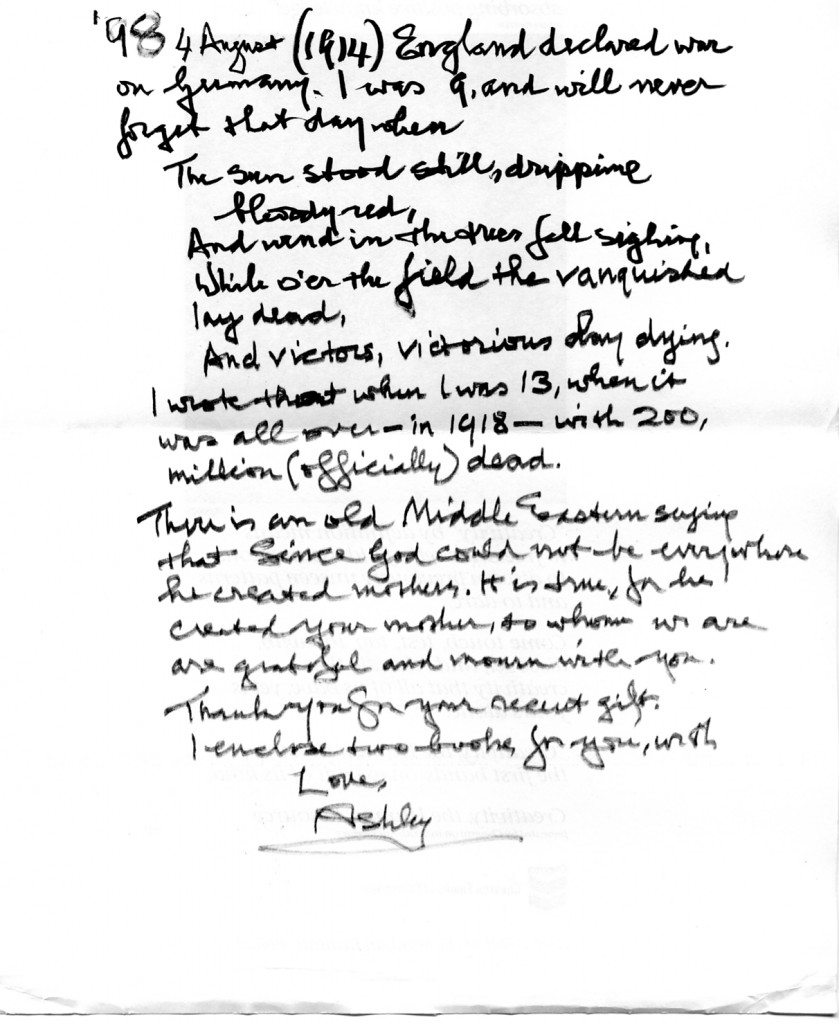

When a child sees or becomes a victim of hatred, abuse, or war they crave love all the more and beg to understand why it’s not forthcoming. The social and historical aspects of trespasses are required for a more complete picture, something terribly challenging for young minds. This next letter has Ashley reflecting on a tragic memory from childhood where he witnessed great violence, which called upon the resiliency of human nature.

In the midst of a painful childhood memory of war, Ashley evokes the soothing Middle Eastern saying “since God could not be everywhere he created mothers.” His heartfelt belief in a woman’s unique capacity for compassion sparked the writing of his 1952 classic The Natural Superiority of Women (which has gone through seven printings). This book was serialized in the Saturday Evening Post, which some claim led to the formation of the National Organization for Women in 1966. In the prologue of the 1994 edition, he defended his use of the word superiority. “My many years of work and research as a biological and social anthropologist have made it abundantly clear to me that from an evolutionary and biological standpoint, the female is more advanced and constitutionally more richly endowed than the male.” His claims caused him to draw the onerous conclusion that a woman has a “great evolutionary mission to keep human beings true to themselves, to keep them from doing violence to their inner nature, to help them to realize their potentialities for being loving and cooperative.”

Ashley lived true to his motto: to be kind, to be, to do, and to depart gracefully.