This oral history of Dr. Thynn, conducted in August 2017, is a follow-up to our meeting at the end 2014, which appears at the end of this update and Q & A. Dr. Thynn moved back, after a two year hiatus in Santa Rosa, to the Sae Taw Win II Dhamma Center in 2014, which she established in 1998. It was, in her words: “the best thing I did for myself”. In this continuing oral history, she explains her decision, the period since her return, current happenings at the center, and answers questions about mindfulness practice in daily life.

Thynn had moved to a senior mobile home park in Santa Rosa, California. Because it was predominately an elderly white population, she found it difficult to relate to anyone. She had one neighbor who became a friend. She describes it as spiritually like a desert. All concrete and a few manicured trees and bushes. She felt out of place, and missed the rustic nature of Sae Taw Win II Dhamma Center, with lots of trees, grass, birds, flowers, and plants. “When I came back, I was in my element; it was really home”, explained Thynn.

As a mindfulness teacher, nature, especially at the Center, serves as an anchor. Thynn tells us that the energy of the trees, the grass, the whole of the environment, the birds and the bees, the wild animals that come onto the property off and on–is such refreshing green energy. As she says. “The ‘grounding’ happens naturally. I felt very grounded…(chuckle) you have to practice mindfulness. There was this very natural grounding. Then there’s the shrine, stupas. So I found myself really grounded and in my element; the peace, contentment, it was out of this world.”

Returning to the Center was therapeutic on all levels. Thynn had left largely because she was physically overwhelmed at the time. She couldn’t sit more than an hour to teach and that’s why she took semi-retirement. The board was taking care of the property. And some of her teaching assistants were teaching. Thynn shared how the break was really good for her because she was very burnt out after 15 years of running the place, the management and administration and teaching.

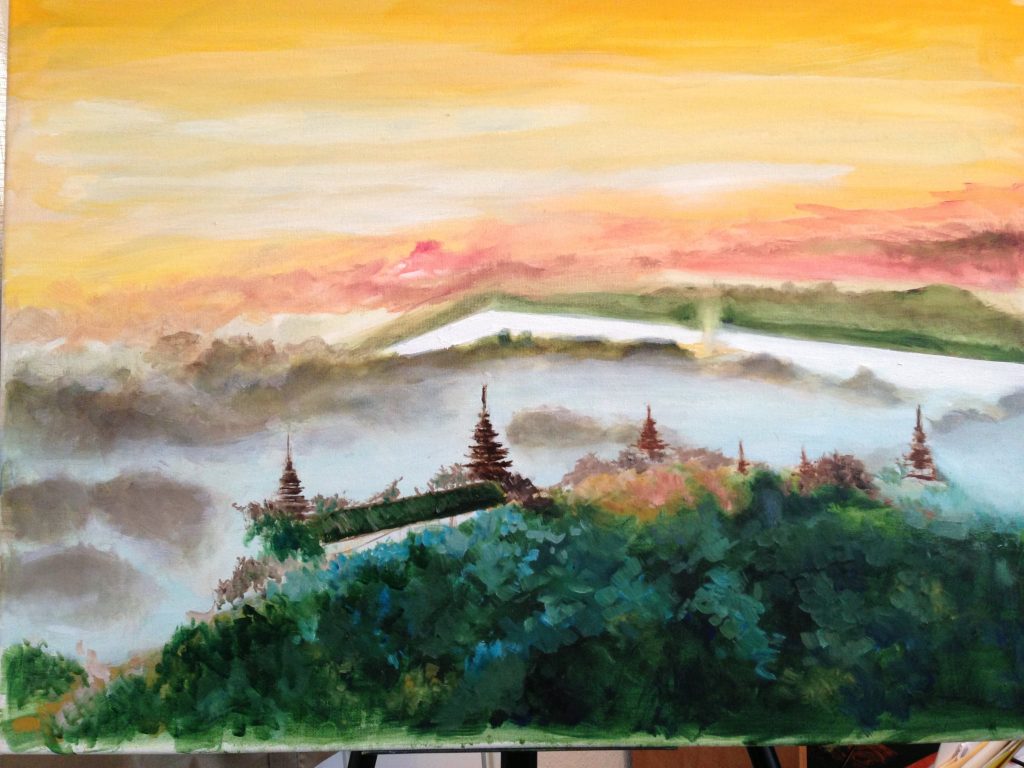

While living at the mobile home park, and to this day, engaging in art has contributed to her well-being. Thynn “reconnected” with her art after visiting Burma in 2014.

During her visit to Burma, she met one of the very famous dissident students of 1988, who happens to be a great artist. There was an instant rapport. She was invited to his home, where she also met his father, who is one of the old remaining art masters in Burma, now in his eighties. Thynn recalls how the house was shocked-full of captivating art; and how she felt very much at home there with him and his father and how art connected them all.

“I was helping him to use his art as art therapy; and he got it right away. I had my people from here send some art supplies that I had on hand; so, I was showing him how to use some of the new medium that he never used. Also, I did a lot of critique on his art. And the art therapy that he did while I was there allowed him to pop out of his low demeanor… You know, he was also burnt out. Just out of prison for twenty years. He couldn’t make his art. He was stuck, blocked. I helped him un-block it…He’s an artist, writer, songwriter, musician, even a playwright, later on he was directing plays. This is a very spectacular artist whose talent ranges all the art activities. I was very captivated by him; and I wanted to help him because he’s one of the most popular politicians now after Aung San Suu Kyi. His name is Min Ko Naing, which means ‘conqueror of kings’.”

Thynn continues:” I started helping him, showing him how to use pastels… then I came back and I started feeling like doing some art. I bought some more pastels and started doodling, from there I started watercolors. I’m very well trained in painting and pen and ink, since I was in elementary school. So I started doing sketches with pen and ink; and then a little bit of watercolor. Then I found out there was a portrait of my son that I had painted many years ago, only half done, so I thought, well, I should finish this portrait. I bought some oils. This started rolling, before I knew it I was really pouring out in art, I couldn’t stop myself. I’ve never been so creative in my whole life. For a whole year I just kept on painting, and painting, and painting–non-stop. Then my little grandson came. And, of course, that completed my healing.”

Dr. Thynn gratefully embraces the revitalizing nature of art and helping to nurture a newborn grandson. The joy of such ongoing experiences requires a degree of vitality. When asked how much vitality is necessary to be mindfully present through daily life activities, Thynn answered: “If you’re still new at it, you need that strength, to make efforts, and you need some level of physical and mental vitality. But I’ve been practicing for over 40 years, it’s part of my being now. When it becomes effortless, it means that you have embodied the practice. And the practice is part of your mental state.” It becomes a default way of being. As she says: “You just automatically drop into recognizing quickly. You know it right away… you know where you are, and it’s not a problem even if it is not where you want to be.”

Such was her time at the mobile home park, where she felt out of sync there–she, nonetheless, accepted it. Then came the natural inclination to come back to the Center because the physical aspects of the property were deteriorating. The whole garden, the landscaping went to seed. The classes needed to be revitalized. Despite there being four board members that tried to see that the rooms were rented out so that there was enough money coming in, just to keep the center going. When she came back she tried to revamp the whole thing: the residency program, the physical structures, the grounds, everything had to be revamped. It took about a year to really bring it to some acceptable level. The grounds are manicured, there is a new picnic gazebo, a play area for children, and ground was broken in March for a new stupa. Repairing the foundation of the (100 year old) Dhamma house, however, remains an ongoing project.

The classes started up again in 2016, as did teacher training. Melissa Titone is now teaching quite a bit. Jane is teaching a group through video conferencing, which is taking off very well. And Dr. Thynn, herself, is doing videotaping of classes and teachings–such as, Bringing Harmony to Conflict, the beginning class, all three courses will be videotaped.

Facebook has been influential in keeping the larger community of supporters engaged with the Center’s projects, especially for Burmese friends. As Thynn explains: “The Burmese community has always been in touch with me, because we kept on doing festivals, although minimally; we had thirty or forty people. But we did keep on having them. So some of my very committed Burmese friends would still come and support us. Now that I’m back at the Center, of course, they feel much more connected with us. And then there were new friends who came in; and I put on Facebook about the new stupa we’re going to build. That brought a lot of new Burmese friends.” [Sae Taw Win II Dhamma Center will be building on site the replica of the very Venerable Shwedagon Pagoda in Burma. It will be called American Dat Paung Zu Zedi.]

The building of the stupa is a costly affair, and the Burmese community has contributed greatly. Thynn formed a committee of Burmese expatriates in the Bay Area (California), and they will be doing a huge fundraising on October 1st in the East Bay near Newark. The stupa is going to be very expensive, Thynn estimates around $100,000. The finished project will be gilded and have a main shrine, as well as six smaller shrines around it. There will be a lot of other embellishments and smaller structures. Thynn tells us the stupa will be 19 ½ feet tall and the base will be 22 feet in diameter; with 7 feet tall smaller shrines, six of them surrounding the main shrine. She says they are very popular features with Burmese Buddhists–the base is like an octagon shape–every corner there will be a shrine, because that signifies the day of the week that a person was born, it’s like an astrological shrine with a Buddha image on top. [The Burmese zodiac employs eight signs in a seven-day week, with each sign representing its own day, cardinal direction, planet (celestial body) and animal; it is known as the “Mahabote zodiac”] The animal for that day will be a hamster, a lion, an elephant. Burmese like to pay respect in the particular corner. Specially, if a person is advised by an astrologer that you need to up your karma by praying at that or making offerings. Thynn has already gotten at least four donors for the corners. According to Thynn, “Burmese love donating to pagodas because the merit is highest when you donate to Buddha shrines.

There was a consecration ceremony in March when they broke ground. Four monks came to consecrate it, and everybody attending took part in breaking ground. Thynn describes the scene saying: “We managed to form eight corners. It was really fun for them too. We sorted out by day of birth. Every Burmese knows what day of the week they were born on. So there was a big line-up: Thursday borns this way, Monday borns that way. So they all lined up and everybody had a go at hammering a stake into the ground. It was really great. Even the littlest ones, (which) was my grandson who was only 5 months, and he was Sunday born–the central stake was Sunday, my daughter was a Sunday born so the two of them did the stake for the center post. So even the littlest one had a chance. And my older grandson was born on a Wednesday and my husband was on that day, so the two of them did their little Wednesday ritual. I was Thursday, standing in line for Thursday.”

When I asked Dr. Thynn when she thought the stupa might be completed, she answered: “You know, this is a very interesting question that I can’t answer because these pagodas–this goes back to my lineage, it’s a mystical lineage. It’s a very powerful lineage. Very much like the lineages in Tibetan Buddhism, the Lamas have great, positive energy, healing powers and so on. And so the power of the lineage itself will carry it. I’m just an emissary doing their work. The energy is just carried by them….The date of the main consecration and the final consecration is always determined by the powers that be. But it will be a very rewarding, interesting construction. The student who built this picnic gazebo will be the main contractor building the pagoda. The top part, which is more or less a sculpturing, and the little Buddhas that go inside the stupa itself, will all be made by a local sculpture. The shrine is going to be hollow inside and we will be enshrining 500-700 little, 10 inch Buddhas. People are already donating to these little Buddhas. That will bring in quite a lot of donations that will offset the building costs. So, along the way there will be enshrining ceremonies, maybe at least two of them. Because I will be installing four walk-in Buddhas, standing Buddhas 3 feet tall inside. I already have donors for all four. It’s really flowing in. Even donations are coming in from Burma.”

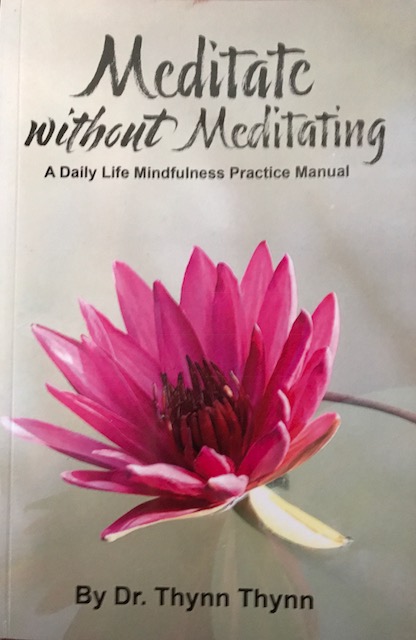

Thynn Thynn’s latest book is now available on Amazon

Q & A with DR. THYNN ON TEACHING AND PRACTICING MINDFULNESS

Q. When you’re teaching are there always new, interesting questions that keep it stimulating for you as the teacher?

A. It depends on the students. How intrigued they are. If they ask very challenging questions that’s very stimulating for me.

Q. As a teacher, would you give us an example of challenging question put forth by a student?

A. Yes, one of my students, her son-in-law committed suicide and she was really suffering a lot; always berated herself for not doing more or recognizing it or preventing it. Of course, nobody knew what was happening. He wasn’t open and talking about it himself. So in class she was going over it again and again and again. It became an obsession. So at one point I thought, well this is not going to help her. So I just asked her straight forward, simple question, I said: “Okay, now, can you accept the fact that your son-in-law committed suicide and died?” That stalled her. It was a very difficult question for her. She stopped and thought about it for awhile and I just let her do it, let her sit on it and asked the rest of the students not to intervene, not to discuss. It’s important not to have any intellectual discussions.

It was very important for her to look inwards through mindfulness. So I was pushing her to look inwards, to see if she could accept it. Why I did that was because she could not accept the fact that he had died through suicide. She was not able to look at it and accept it. So her mind was turning round and round and round, and she was suffering a lot. She had two little children, so that made it worse. So she took quite a while, maybe 15 minutes or so, and finally she said: “Yes, I can accept it.” After that she went quiet.

Q. So sometimes with difficult questions the teacher ends up inquiring with the student. You’re asking the student are you able to do this or that, rather than have them elaborate?

A. Allowing themselves to discuss it. Well, it’s a tricky situation. I have to be very aware of my relationship with the student. I can’t do that with a new student. She was an old student who had a lot of confidence in me. There has to be a lot of trust on both sides. Some of my students earlier had coined as, “being put on the hot seat”. It’s like a Zen teaching. So I bind that person there and limit their thinking. Toward a very pointed direction, which is usually toward their own inner state of mind. It is designed to stop discursive thinking; stop the run around and just watch their own mind. So I can use different kinds of questions, but the whole idea is for them to turn inward, and see if they can accept it or not. It means that they have to look inwards.

Q. It almost forces them to investigate how they’re feeling.

A. Exactly.

Q. And it gets to the fundamental question of accepting it means you are able to recognize it happened, how it makes you feel, and letting it go.

A. Actually, like the Zen masters usually do, they are extremely clever and skillful in doing this kind of what they would call interpersonal transmission. I was just pointing out or directing her attention into herself and seeing what is there and whether she can accept that. Accepting the passing…the suicide element was the main thing.

Q. She was feeling guilty.

A. Yes. So the technique was meant to cut through all those mental constructs and mental run around, to stop that, and help her to really look into herself directly to where she was stuck.

Q. What about the student who says, “it’s too painful, I can’t look, I get too anxious”?

A. Oh, I would stop. I would go one step further back and say, okay, just look at your anxiety; and not think about the incident.

Q. But it hurts too much to watch my anxiety.

A. Then I would say, okay, take a break. Go home and listen to some music or movie.

Q. So, distract, and then at some point… (re-engage).

A. It depends on the person. If they want to come back, they come back. If they feel it’s too much, they don’t want to do it, then it’s their decision. You can’t force it. On my part, I have to be very careful on how strong the person’s mindfulness is and how ready they are to do this kind of work. So, I might not do it right away when they talk about it. It might take one or two sessions. Then when I feel like they’re ready, I might. It’s very much intuition on my part.

Q. How important is it for a person to go through (the process) having compassion for themselves. Holding themselves in this awareness of compassion for their experience before they can….

A. Well, you know, I always go for insights. When they can really retrieve or let their insights arise compassion for themselves follows that. If you focus on compassion alone, it will feel good for awhile, but then it will not cut through the mess–the mental, the emotional, dark block.

Q. Right, it’s almost like putting on a false positive…being too positive rather than realistic.

A. Yes. I don’t really do that unless a person is someone who can’t handle it. I might do that–metta meditation for themselves, compassion for themselves–give them a little leeway, a little rest. But, all in all, in the Buddhists’ practice, it’s always panna (in Pali) or wisdom. Tibetan Buddhists call the Manjursi sword. It cuts through all the layers of delusion, emotion, stress…all that. That’s why, if they can handle it, it’s extremely important to help them to cut through the so many layers of distress and suffering.

Q. What are the primary ingredients to get to that wisdom?

A. Mindfulness and equanimity. How strong the mindfulness practice is. Once they can cut through, because the whole practice you all have been studying is to develop equanimity. So through equanimity and strong mindfulness and steadiness of mind (samadhi), if these three ingredients are strong enough you can cut through so many layers of distress and emotions and so on. I always like to quote, A Hero’s Journey by Joseph Campbell–it’s like going through Jonah’s Ark where you almost face literal death of the ego, and then you find a pot of gold under the belly of the whale. This is like that, it’s like going through the belly of the whale and cutting through that darkness, and at the bottom is the answer or the boon.

There was another incident I did many, many years ago with one of my older students. She was very worried about her son who had severe ADHD and he was coming back from somewhere on the bus. She was worrying the whole time. So I asked her, “even if he dies from a fall from the bus, can you accept it?” It took her awhile to get through that, and finally she did. I know it was very heartbreaking. I could be looked upon as being quite cruel. You know, that’s the final challenge.

Q. Yes, it does seem that way. I often, as a mother you think about all your family or your close friends, whatever, and you just (know)–anything can happen at any time, can you accept that? This is an impermanent life for all of us. And impermanence is really one of the greatest teachings.

A. It is.

Q. So the woman who lost her son-in-law from suicide, she needed to completely detach from any part she might have played in it. That wasn’t real. It was his decision. He did it. That’s just a story she made up in her head that she might have been at fault for whatever reasons.

A. Or she was thinking she could have helped, to prevent it.

Q. That’s a natural place to go.

A. Right.

Q. In Catholicism, they would say guilt serves a purpose because it keeps you in check. It asks you to look at your morals or value judgements. And are you coming from a moral virtue. So it serves a purpose in investigating where we’re at, but it’s the clinging that’s the problem.

A. Yes, it is. Then the clinging is an obsession. So the person goes round and round in her or his head, and it never ends. It’s like a wheel turning over and over again. So this is like putting a break on the wheel.

Q. And what is it? It’s our mind, it’s our push to be a good moral human being and to learn. I don’t know…it’s an emotional pain. And some people…it’s a mystery what feeds, what motivates, I think, somebody to continue this and go over and over…

A. Well, in the Buddhist term–it’s delusion. Thinking, the delusion, that it’s her fault…so, it goes back to the ego. The delusional ego, thinking that she can be in charge. She could have prevented it. Although it is a noble thought. But, you know, a person’s karma is his or her own karma. You can affect very little or none at all.

Q. How do you explain sympathetic joy or, moods are contagious, and in that way we have a certain responsibility to make sure that we come to this moment in an open, non-judgmental way, which is what mindfulness is based on. So we have to take personal responsibility to how we’re showing up, and it should be in an open compassionate way.

A. That’s why I keep telling students in class–that you can not isolate mindfulness just by itself. There are other teachings that the Buddha had given, like, for example: the teaching of impermanence; the teaching of non-self; the teaching of suffering. All these three are combined in your own experience. Why does a person go round and round and round? It’s because of the self. The delusion of self. And the delusion of self goes to think that: I can make it permanent. That person wouldn’t have died if I had invested in it…

Q. Wanting to control…

A. Yeah, again it’s the ego. And the delusion that you can control somebody’s life. That’s a delusion.

Q. That’s a real difficult place for people to come to the acceptance that life is ultimately uncertain and groundless.

A. Yes.

Q. So how does one accept that?

A. There’s another element that Americans, Westerners cannot pull in is the karma and rebirth. Because Westerners don’t want to look at rebirth. It’s here and now. But you cannot isolate here and now as the sole answer, the only answer to that. No, because a person had come to this point in time, it’s a summation of this life time’s past experiences as well as the past life experiences that has brought the person to this point in time. And in this point in time, how much can you influence that person? Not much, not even your own children. When my son was diagnosed with cancer, that was about 17 years ago, of course I was suffering a lot. I was grieving, most of the time when I think about it, and finally it was hard to bear. Finally, a breakthrough came to me. That was when I started to realize that, oh yeah, he brought a lot of bad karma from his past life, and it has nothing to do with me. He has to go through the ravages of his past life. That was a huge relief. That helped me to separate myself from him. And for Westerners it is so hard to accept past lives and future lives, rebirths.

Q. Yes, it’s not part of our story, we never heard that growing up, it’s never been part of the cultural narrative.

A. And my son is still alive and cancer free after 17 years.

Q. That’s wonderful to hear. He’s in the Philippines? Or he’s in Thailand or here?

A. He’s kind of roving around Asia. It’s also, let’s say I became almost psychic after meeting with my guru. And I could look into his (son) past lives and I tried to explain to him why he had cancer. Because for someone like him with cancer, the question is “why me, why me?” And it was very hard for him to accept. So, when I told him about his past lives, which resulted in him having cancer in his lifetime, he felt so much at peace. Because there was a reason.

Q. Yes, and it’s nothing he did.

A. I mean, that was in the past, he didn’t do it this lifetime. He did have to go through the result of his misdeeds in his previous lifetimes. So that gave him a reason why, and answered the question, why only me? And he was able to take full responsibility for it. And that’s how he became at peace with cancer.

Q. This is part of the Buddhist’s teachings: Buddha talked about karma…

A. Oh, yes, karma and rebirth. In the Abhidamma there’s a whole slough of things there. Why is it that I have such a difficult spine? There’s like four places that are deteriorating, but my other vital organs are pretty good. And I found that I was in battle in one of my past lives, and I had injured leg and limb. And my daughter, when she was in medical school, she was in residency and the rotation she had to go to in obstetrics and gynecology, and she was asked to assist in an abortion. She asked me whether she should do it or not, so I told her about my past life, the result of my past life. I said, you think about it and make a decision whether you want to assist in the abortion of a human life. So she refrained from it.

Q. Do no harm.

A. Yeah, do no harm. So that is a big chunk of teachings that Westerners couldn’t handle or accept.

Q. Is there any way to help them that you’ve found?

A. Well, it’s very hard. Unless the person has become somewhat a psychic. I could see into their past lives. I think that there is a way to do it, like past life regression through hypnosis. I’ve been reading the books and writings of someone called Professor Brian Weiss, he was part of Cornell University. He is world famous now, he was on Oprah. He was a psychiatrist and doing just clinical psychology; with one woman, he couldn’t help, for six months she had difficulties. So he, out of a whim, in one hypnotic session he said: go back to the source of your suffering. And that opened up the whole thing. She went back to her past life. He didn’t design it, he wasn’t really doing past life regression. But she went by herself there. And she came out with all kinds of stories why she is suffering in this lifetime. So he started doing past life regression with her and in six months time she was cured. And out of those sessions, he found that he was one of her teachers in one of her past lives. And so he became very famous for past life regression, and he wrote several books. And I saw him on Oprah. He did a regression right there on TV. It was very interesting in that session too. She said she was always afraid of dogs, it was just very unusual, she couldn’t handle dogs, didn’t want to look at them. In her regression, she said she went back to a time when there was a flood and she couldn’t save her children. She tried to save them, but they died during the flood. So that was carried over to this lifetime where dogs symbolized her children in a past life. She didn’t know why she was so scared.

Q. So, in the understanding you’re able to accept. When you get some resolution about why, or some insight

A. Yes insight into why you’re carrying that memory, and carrying that karma.

Q. Some people can skip that whole need–to maybe accepting whatever… or is it helpful to investigate anyways?

A. Yes, it is helpful. But you have to go to a real top notch hypno-therapist who has a lot of experience with past life regression. You don’t want to do it with any Tom or Jerry. In his book, there was an older gentleman with heart problems, he was very angry at his daughter. And his daughter was going through some illness. And he didn’t agree to her boyfriend. And he was a mess. So when he came to the professor, in his one past life regression he found that his daughter was his lover in his past life. He was really very much in love with her but she died in that lifetime, so he didn’t get to marry her. So in this lifetime, she was reborn as his daughter. So he became very obsessive with her, because he carried that sense of loss, so he was very afraid of losing her again. So he became very possessive. And they were at loggerheads. She even became ill because of that, and he was having heart problems. Out of several sessions, he was able to let go of that obsession of her; and she also became much better. And finally he allowed her to marry her lover. Both of them, their health became much better too, and they were much happier.

You see, that’s why Westerners, I think are missing out a huge deal. The key part of their life from past lives. Which they could have if they could make that bridge. It would resolve a lot of suffering, a lot of problems and their relationships in their family or even friends.

Q. Sure, and even if… I’m wondering if it would be effective even if they went in doubting, but they got the story that made them see it in a new way that was liberating.

A. Yes.

Q. Because it’s about reframing a story that hasn’t worked for you.

A. Right. That’s a huge missing piece that needs to be uncovered, and related to. Because it relates to how things are for you in this lifetime, which has no answer, no solution as it is.

Q. Right, and people have so much pain they hold onto, so much.

A. And the pain could be from their past lives, which has no solution here, unless the person became aware of that story and could relate to it and let go. So all the therapy can only resolve this lifetime problems, but not the past lives. Like my son, he’s now totally at peace with his past lives and he’s moving on. He’s even repaid some of the debts, karmic debts he accrued.

Q. I get asked this and sometimes I don’t know how to answer: what’s your cutting edge, what are you working on right now in terms of getting that ultimate liberation and insight?

A. I’m not working on anything.

Q. It’s a spontaneous allowing.

A. Letting it flow.

Q. It’s a good time…I don’t feel conflicted, my life seems to go okay and when it doesn’t it seems like the accepting part, just pausing, just allowing it, giving yourself enough time to create that distance is really critical. Just allowing you to step back. Because your first instinct might be to get angry at something or defensive–it just doesn’t take that much time to start witnessing how you’re feeling.

A. Exactly.

Q. And if your mind, if you’re intent to practice, I think that is crucial. A. Yeah, when you come to an obstacle or something that bothers you, then it’s always good to reflect on the present situation and see, okay, what is that is hemming in? When you look at a bird’s eye view of your life you’ll find where you’re stuck, something that’s not resolved. Then you just do what you need to do. And your life will be the way you want it to be, unless you have some past life negative karma that needs to be resolved.

Q. And then that shows up sometimes out of your control.

A. Yeah, it does.

Q. So does there seem to be an edge for you or a challenge in your practice, something you’re focusing on in particular.

A. There’s really nothing that’s too difficult for me. Because after 45 years of practicing mindfulness is part of my psyche. But I have to be very careful, it’s my body. I don’t over do things, I have to relate to the limitations and work with it and to be very sensitive to what the body needs because you can tend to over do things. At the moment, it’s not too difficult, but the effects are usually delayed. Like my little grandson if I carried him too long then that evening I would suffer, my back would suffer. But when you become very sensitive to your body and its needs and how you are and where you are in your daily life, then you try to find solutions. Like, I just bought him a walker that he can sit in, and it also has a lot of toys in front and in back of him. So, he gets very excited with the walker when I put him in it, and I can still take care of him. I sit in front of him we play, he laughs. So it’s becoming very sensitive to your needs and the needs of people around you. So I can babysit him for 15 or 20 minutes or half and hour depending on how long he can stay there. He gets tired of it too, so then he’ll make faces or cry or whatever, so then I take him out. So these are kind of aids that I try to get to help him and to help me. Because that is what is important–to become aware, to be sensitive to my body so I don’t extend myself too much.

Q. That’s one of the foundations of mindfulness–mindfulness of the body?

A. Oh, yes.

Q. The body seems to be a common window into…

A. Yes, into your own suffering.

Q. It’s a good teacher if you allow it.

A. I don’t particularly think that or set up intention to practice. Because the practice is with me 24/7 and I can draw on it at any time, any where. If I’m speaking to you now, if my ego arises I become very aware of it. Or if I’m distracted I become very aware of it and bring it back to the moment. You can call it effortless effort.

Q. When we’re practicing mindfulness there is suppose to be this choiceless awareness so to speak; you’re allowing things to arise as they are, a certain allowance, but at some point you’re going to pay attention to one thing or another, you’re going to focus your attention–so it loses the choiceless aspect–you’re open to the experience but at some point the experience dictates the most prominent sensation.

A. Yes, the most prominent sensation in your mind or in your body…there are five senses. The mind is always the sixth sense, that’s in the teachings. So, if you’re on it, you’re very sensitive to all these things happening in your mind or in your body–that is the practice.

Q. And some people might say that it is so overwhelming, I hear I’m suppose to pay attention to the breath, and I’m suppose to pay attention to the body and the sensations, and my feelings, my thoughts, and I don’t know what to do?

A. Actually, it’s simple. You just focus on what is the most prominent in the moment either in your body or mind or out there through your senses. Not thinking about all the practices that have been taught. Right now is just one thing at a time. And you make use of that moment and not think about what is being taught. Right this moment is your experience and that experience is what you work on without getting guilty or not doing the right thing. Because anything is game for you. I’m talking to you and if I’m distracted by the birds, I know I’m distracted so I have to come back to your words and listen to you. Like we have children playing in the swimming pool, of course I can hear them, but if I focus on your questions they fade into the background. But if I focus only on them, then your voice and what you’re saying will be out of my attention.

Q. It’s almost a misnomer that people think that they can multi-task. Your mind is actually split second changing.

A. Yeah.

Q. And you’re not aware of it.

A. Right. You can multi-task if it’s not a very important thing that you’re doing. Like when I’m eating, I may just go on Facebook. I eat, I enjoy the food, and then I go back to it. It’s only single action. If something is automatic and you don’t really have to pay a lot of attention….driving.

Q. What would you say to a person who says: people always say, “go back to your breath as anchor when I’m anxious”. I get anxious a lot, but just focusing on my breath makes me more anxious, that’s what makes me anxious.

A. You know, the best thing is to use your tactile sense. Like washing dishes, rub your hands. I will tell my students, if there is nothing else just keep rubbing your hands, and touching your hands and put your attention there.

Q. My mom was an obsessive compulsive worrier in a very clinical serious way, shock treatments, and she would ring her hands all the time.

A. That is one way, she is choosing something that works for her.

Q. Right.

A. It’s real clever. It’s very intelligent.

Q. And it’s also a natural tendency though, when people are nervous or something you can see that. So it’s your body’s automatic intelligence.

A. Oh, yes… you know, I had a student once who was going to France and were involved in a lawsuit with his ex, and he was very anxious and he asked me what to do when he went to the courtroom. I said, you just count, one, two, three, one, two, three, one, two, three, just keep counting. So that drives away all the emotional things. And he did quite well.

Q. It’s almost like a mantra then.

A. Yeah. You can use it as a mantra, or God, God, God, angel…

Q. How would you describe the difference between meditation and mindfulness?

A. Mindfulness is one form of meditation from the Theravada tradition. Meditation is a very generic term that encompasses all kinds of contemplation.

Q. One pointed.

A. Yeah, like the Dervishes, they’re meditating while they’re twirling. The mantra. All kinds of sound, om or whatever. They are all meditative states, contemplative states. Mindfulness is one form that arises, that came out of the Theravada tradition. Even in the Theravada tradition there are forty types of practices, tranquility practices–metta, compassion, the mantra is also a calming practice.

Q. That’s why Jack Kornfield feels like you have to add an “s” onto the word meditation, there are meditations; there’s not one sport, there are lots of sports.

A. But mindfulness is a very particular type because it has several elements in it when you practice mindfulness.

Q. And how important is the curiosity? When you’re approaching the moment with curiosity?

A. Well, if you’re open enough curiosity is an asset. Depends on whether there is fear in your curiosity. Whether there is too much ego invested in it.

Q. Well, that’s true, because you can approach curiosity in many ways. When my mind gets curious it goes to–I wonder how I’ll do on this musical piece…

A. Then it’s fear based.

Q. Oh, not just open, I wonder how… it’s seems like it releases fear for me. It seems like rather than say, oh, I don’t know how I’ll do…

A. If you recognize the fear and let go and the curiosity is left alone, then it works very well. Like for example, I have a mind that is very curious with all kinds of things, especially like politics, I’m very curious. And I like to study what it is, what’s happening. But my practice helped me to not insert ego into it. My people, my country, my party, so that helps me to look at things in a more general way…. It’s just politics. It’s a process. Like a play, going out there. And just curious how it’s playing out.

Q. There’s a lot to be curious about, especially here in America.

A. You can also choose where you want to put your curiosity. I don’t lose my time or let my emotions get in the way. It’s just a process.

Q. Some people get very, very angry. So is that a jumping off point for getting involved maybe? So, turning unwholesome traits, like anger, or feelings, into wholesome ones — you balance it — so we bring compassion to the anger. One might say, ‘I need to do some action”.

A. I’m not very big on compassion purse, because compassion is a normal result of the arrival of wisdom. Wisdom will bring compassion in its wake. It will be there. The most important thing is to allow wisdom to arise in oneself.

Q. If they’re really angry about the political situation, they just can’t accept that they’re rolling back regulations, or climate deniers, or whatever it is…

A. You know, I wouldn’t worry. Because everything that arise must fall. There is always a cycle, and things will adjust in its own way. There are always checks and balances, especially in American politics. There will be checks and balances, compared to countries like with military dictatorships where there are no checks and balances. You’re lost totally. I’m quite amazed at American politics and politicians, they’re not afraid to go out on a limb and investigate the President of the United States, and that is a huge thing.

________________

Dr. Thynn Thynn’s Oral History conducted Winter 2014

Dr. Thynn was born and raised in Burma to conservative Theravada Buddhists. When she was 25 and a medical intern, she started studying the Abhidhamma (Buddhist psychology and philosophy). Being a young doctor, the hidden parallels with biology and some psychology in the text excited her.

I was born and raised in Burma to conservative Theravada Buddhists. When I was 25 and a medical intern, I started studying the Abhidhamma (Buddhist psychology and philosophy). It became almost like the great love of my life. Being a young doctor, the hidden parallels with biology and some psychology in the text excited me.

It is a treasure trove of teaching that not a lot of people in Burma are familiar with. I had started to sit in silent meditation at a monastery each Sunday. During that time with the sitting, an immediate awareness of my feelings developed—strong emotions, like anger and frustrations—would fall away. I felt freer. But in Burma, if you’re a woman, you don’t go to a monastery by yourself; you have to have a companion, either a woman or a man to accompany you. I stopped going, when it was difficult to find a companion to go with me.

The impetus to move to the capitol of Burma, which at the time was Rangoon, came over me. I met a writer there who, because of the way I was answering his questions about health and the health care system, encouraged me to write. I gave it a try, and he helped me get published in a local newspaper. I liked this engagement with public health and the sociology of medicine, so I took a diploma course, and soon jumped the fence from general medicine over to public health. I worked in civil service for 15 years in Burma, and taught under grad and postgraduate classes in public health.

During this time, I had started painting. For a year, I studied with a Burmese master named U San Win, who was trained in England and France. I was invited to participate in an all women’s exhibition in Rangoon. It was an historical event. There had never been an all women’s exhibit before. I also met a gallery owner who happened to be an artist as well as a dharma bum, and he had started a very progressive dharma group. They were talking about Zen Buddhism, Krishnamurti, and Upanishads—this was the 70’s in Burma, which was a very conservative Theravada Buddhist country (it was almost as if monks were evangelists). I joined the group, and they took me to meet two of their teachers. They were teaching practice of mindfulness in daily life, meeting and training with them changed my life. The traditional, classical explanation of mindfulness, from a Theravada Buddhism point of view, is a very comprehensive awareness of the moment, either of your own thoughts and emotions or the surroundings. It’s beyond ordinary paying attention— you’re also realizing, in that moment, the impermanence, suffering, and non-self aspects of reality. The specific qualities of clarity, equanimity, and wisdom or insight arise; it brings forth love and compassion.

Then I moved to Bangkok where my husband was assigned a job working with the United Nations. We had two babies and I became a full time mom; eventually I began to work for the United Nations (U.N.) and the World Health Organization. After about four years living in Thailand, I began to teach, I was 46. Because of my writings on Buddhism and meditation, someone came to my house and asked to be taught—and a teaching career started. A small dhamma group of 6-14 of us went on meeting weekly for three years. I would write down what we were discussing in the group, and that became a book manuscript. That was in 1986 through 1990. Then we moved to the United States, when my husband was transferred to New York U. N. Secretariat.

We settled in up state New York, in Scarsdale, Westchester County. I was very sick then, and that was the biggest challenge of my life. Menopause contributed to an already established condition—a disorder of the inner ear—a variant of Meniere’s disease that causes vertigo and affects balance, but not hearing. I started having severe vertigo; at the same time I was raising two young teenagers. That’s when my mindfulness practice really intensified. I just put my attention on the sensation of dizziness, not letting any thought enter into my mind, or fear, or worry. It allowed the natural history of the symptoms to abate. I had some very good treatment in specialized care for an inner ear disorder, which helped my recovery.

In 1991, I started visiting California. Back in Thailand, I had had a stream of meditators that would come to see me; two were women doctors from northern California. When I visited them in Berkeley, they had already made some arrangements for me to speak to a local group, and one in San Francisco. During those engagements, I would get other invitations, and a video of my talk was produced. Teaching all Americans was very exciting. I started doing an annual teaching circuit; then Spirit Rock Meditation Center invited me. Shortly after that, my book came out: Living Meditation, Living Insight (available free download online here: http://www.buddhanet.net/pdf_file/livngmed.pdf.; hard copies can be ordered from Amazon.)

My students all started asking: “are you going to start a dharma center?” That’s how I began to look for a place to start a center. My son was still in high school, and my daughter was already admitted to Stanford during that year—so it all sort of fell into place. In 1996, we moved to Sebastopol and my health got much better with the more ideal climate, and the wonderful, open-minded neighbors and community at large. When somebody donated $5,000, we started a non-profit, religious, Buddhist foundation, and found property in Graton, California. I started to do fundraising among my students in New York and friends all over the world, and relatives in Singapore, Burma, and Thailand, and a lot of my old students from the United States. We bought 4-acres with an old ranch house, nearly 100 years old, with no insulation, no heating—it was in total neglect. I had to educate myself in construction, land ownership, building codes, and finances, which added to the challenges of starting a center. The house was remodeled to have eight bedrooms; with a studio attached to it. We rented the rooms to pay the mortgage. I knew that I was going to face a lot of challenges, but I had blind courage. I am the kind of person who loves to rise up to meet the challenge. The center was named Sae Taw Win II.

I began teaching; I was 59 and already having health challenges. I was developing the property and living as a yogi in the Theravada Burmese tradition, which means semi-renunciation, not getting involved with too much social life. Then the student population started to grow. The most challenging aspect of all this, initially, was having residents there as paid tenants. We found that our guidelines for living communally were not sufficient, so we learned as we went along. All the issues and difficulties, from construction and finances to inconsiderate tenants, sometimes seemed insurmountable. But somehow we moved through it, helter-skelter. It was an organic process, entirely. It was an adventure of falling flat and picking up again.

To be the first woman dhamma teacher to set up her own center in America, and also be the residential teacher was a novelty for the Burmese Theravada tradition. I started with about 10 American overseas students. That meant that I had to push through the glass ceiling. When I began building a number of cedis (traditional Buddhist shrines) in 2001, the Burmese in the Bay Area started to come to the center. Ten years later in 2011 we built 28 shrines within three months, which was an extremely gratifying experience. Young Burmese college students would come and have retreats with me and invite me to give talks at their college.

I existed between two communities: American and Burmese, which was another challenging area of learning and adjusting. When I was studying with my teachers, they never held classes or retreats. You sit with the teacher the whole day, offer them meals, and it’s through question and answer and dialoging and conversations that we learned. I found Americans need more structure, as they are more intellectual. I started structuring my teaching sessions. Classes became highly effective. I designed three courses with a lot of experiential training. My goal was to offer the methods, the learning takes place at home in the student’s own life. I was working and concentrating a lot on these teaching modules, and soon after some of my senior students started to train as teachers. I loved teaching and teacher training: it was my bliss. Teaching Americans, I could be open and gregarious, and I really enjoyed that: (the Burmese community is fairly conservative).

I was really concentrating and focusing on developing a local teaching program, and building a dhamma community. I traveled a few times to different centers and places in the U. S., Canada, and Australia to teach. I was doing all this with health challenges, and I eventually had to stop teaching away from the center. At the same time, I was supporting and taking care of my son, who had very deep depression following an episode of cancer. He was at the center with me for nine years, when I was busy crafting the courses, managing, fundraising, teaching, and running this whole center and teacher training. This was a new development in our life; even as a physician, I had never treated a clinical depressive. So, my burden was doubled. And my own health was not robust. Through the practice, I could pull myself up from a depressive state very fast. But I have learned to let my emotions, like the dizziness, just be observed without adding any discursive thinking. That is how I’ve dealt with some trials and tribulations of my own, or in relationships. It’s a matter of noticing conditioned patterns of behavior, stopping, and just listening to the others without letting my own angst or anything else intervene. The benefits of the practice have helped me to tide over difficulties, especially during trying times.

Much was going on at the center besides the teaching retreats; we had ceremonies, festivals, and rituals regularly. In 2009, we started producing classical theatrical plays on the life of the Buddha. One of my old students and neighbor happened to be a professional theatrical producer and owner of a traveling troupe, and we started writing a script together. We were invited by the young Burmese students to go to the San Francisco Bay Area and perform. The Burmese community couldn’t believe it—it was a 3-act play with full costumes. The cast was 90% American students and the rest young Burmese students. It was an over night success. Unintentionally creating these plays grew to be a passion of mine. Eventually the cast got the theater bug too.

I had planned on retiring in 2018, but by 2010 more health problems forced the issue. I retired last year after almost 15 years living and running the center. Earlier, some students thought that I should write another book, so I’ve got a manuscript nearly completed. I also returned to my art, doing pen and ink drawings, pastels, watercolors, and oils to while away free time. I’m not involved in running the center anymore, but I supervise and try to keep things going. Getting involved with art is very therapeutic for me; it gives me the portal for my creative juices to run. I’ve been painting helter-skelter for the last year. I found that, at this time in my life, this is my true bliss, my true authentic self.

But what is more blissful still is the arrival of my very first grandson. Khine was born in June 2014, and he has changed my whole being, so to say. The child is delightful. He smiles at everyone. Even if he is crying, when he sees me, he will stop and smile at me, then he goes back to crying. That’s enough to make grandma’s heart melt. Having this little baby, with its own aura and kammic traits, is a very precious gift. The family and I, we’re just delighted to receive him and be a part of his life. He also brought the family closer together. He makes me want to live to be 100 years old.

My retirement life isn’t really retirement; it’s just a new chapter in my life. My grandson keeps me going, as does my art for now and, as always, my devotion to the Theravada Buddhist practice of mindfulness in daily life.